Is it because the monsoon this year was exceptionally harsh and the reality of our cities and urban landscape was laid bare for us to, see?

Is it because the monsoon this year was exceptionally harsh and the reality of our cities and urban landscape was laid bare for us to, see?

Or is it that now after our swanky airports, refurbished railway stations and public venues, extensive expressways we aspire for our cities and townships to be also of a certain standard?

So, why do our cities appear poorer than we really are? Even the privileged sections barely escape scrutiny. While they may be better than the ‘other parts’ they still fall far short of what we aspire to.

In the early 90s on a visit to the UK some friends invited us for a weekend to Milton Keynes, a two-hour train ride from London. Conceptualised in the mid 1960’s and developed over the next decade we were warned by old Londoners that it was new and soulless.

Expecting a landscape cluttered with construction debris, half-finished pavements and dividers, a garbage disposal system still not in place were simply stunned at ‘new’ Milton Keynes right from our arrival at the station to their home.

It was evident that it was a township that had been meticulously designed and planned and over the weekend we saw more that was so pleasing to the eye and calming to the mind.

Riverfronts and restaurants, theme parks and sport facilities, woodlands along seven lakes, theatres and museums, school districts and residential areas, High Streets with shops and pubs…laid out in a radical grid plan, comfortably taking in large tracts of farmland and undeveloped villages, also respecting its rich history of human settlement since Neolithic days.

It is said that “Milton Keynes has stood the test of time far better than most and has proved flexible and adaptable” when it was conferred the status of a city in the year 2000.

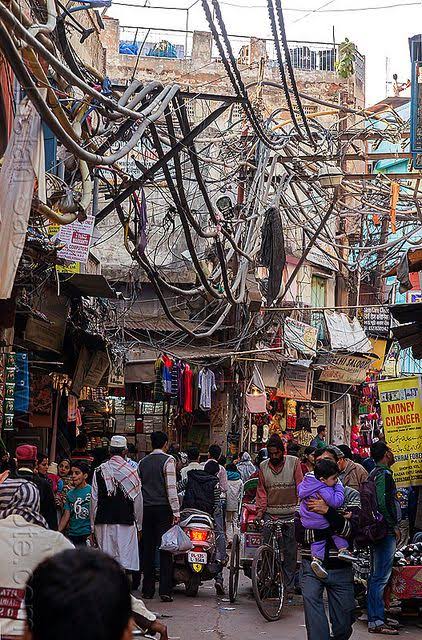

Around the same time, Gurgaon emerged in stark contrast as a chaotic sprawl of glass-and-chrome malls, flanked by garbage dumps and barren plots.

Instead of drawing on the expertise of top architects and planners to shape a cohesive urban identity, the city devolved into a disjointed cluster of buildings, broken roads, and crumbling pavements.

This concrete jungle, largely devoid of parks, green spaces and playgrounds, stands as a glaring testament to how *not* to plan new townships.

In his autobiography *Against All Odds*, DLF’s KP Singh recalls how Rajiv Gandhi granted him carte blanche “to create an international city.”

However, it is evident that the collaboration between developers, bureaucracy, and a provincial municipality resulted in disastrous planning.

Land was acquired piecemeal from farmers, with little attention to the natural topography, leading to a lack of essential drainage systems. Water bodies were neglected, and urban sprawl was prioritized over sustainable development.

Today, Gurgaon is heavily dependent on tubewells that drain its rapidly depleting groundwater and diesel generators to keep the city running. Luxury apartments rise on cramped plots, surrounded by slums, welding workshops, and glitzy liquor stores, a disorderly maze of parked cars and unruly traffic, With minimal policing, a sense of insecurity loomed over the new township.

In the early days, a ‘Pajero sub-culture’ emerged, where newfound wealth met young men of agrarian roots, often on the prowl for trouble during their nights out.

Rough edges were further underscored by the stories of a certain farmer-turned-politician-turned-builder, infamous for starting meetings with disgruntled clients by placing a revolver on the table.

This, indeed, is the embodiment of a soulless concrete sprawl—lacking character, charm, and identity.

The question is why, when there was a new canvas, a new opportunity?

Why, since Independence, have our leaders allowed city planning to be dictated by political whims?

Other nations who became independent around the same time such as Singapore, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, even Morocco have paved a different path, focusing on cohesive urban development.

Meanwhile, our cities, from hill stations to metropolises, have descended into shameful urban ugliness.

And before we rehash the same excuses of population, size, diversity we did not even do it even in pockets, small manageable tranches – with only two exceptions Chandigarh and sections of Indore.

For instance, the arrival of the metro – albeit a century late – has brought immense relief to commuters. Despite the chaos of ongoing construction that our overcrowded cities must endure, people remain grateful. The long-awaited promise of better transportation and an improved quality of life far outweighs the temporary disruptions.

With every rule in the town planning book flagrantly violated, often under the ‘watchful’ eyes of those ‘on the take,’ one can only imagine the devastation a natural disaster would unleash. In such a scenario, first responders would struggle to navigate the chaos, unable to reach those in need, further compounding the tragedy.

Yes, we now see the truth.

They didn’t give us better cars because better roads would have had to follow.

They delayed satellite TV for years, keeping us stuck with a Soviet-style state television, fearing that with more knowledge, we’d see more, question more.

They convinced us that we were too poor for a modern mass transit system, leaving us to cope with rickety buses and poorly maintained auto rickshaws.

They told us that an LPG cylinder was a luxury beyond our reach so piped gas was an unrealistic dream.

They gave us urban sprawls and low-cost housing fit for rats reducing us to beings stripped of aspiration, making us suspicious of progress, comfortable in stagnation.

We were taught to be grateful for what we had. And those who weren’t satisfied? Well, they were encouraged to leave for greener pastures abroad.

But now, this new generation – unburdened by the scarcity and hopelessness of the past – must reject the voices of those well-fed dinosaurs. The ones who first complain about a lack of infrastructure, only to mourn when a new bridge threatens the livelihood of boatmen. This generation must break free from the suffocating grip of those who, for so long, tethered us to a limited station in life.

They must pull away from the dusty confines of tired imaginations and, even more dangerously, from the sinister agendas that sought to hold back a nation ready to leap forward.

The youth must demand, seize, and lay claim to what they rightfully deserve – bullet trains, cutting-edge infrastructure, innovative technologies, and a quality of life that transforms their future and cities. This is their time, and they must not settle for less.

A mission to transform at least four metro cities and eight tier-two towns, following a comprehensive master plan, could set a standard for the next century.

There is still hope for townships such as Gurgaon, to adjust their sails and change course. It only has to be removed from the vice of an incompetent bureaucracy and municipality leaving it to domain experts to deliver high-quality, simple town planning essential for crafting urban spaces.

The bitter truth is that it was our forefathers who gave the world the grid-plan of Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa.

That said, it’s crucial to emphasize that this vision can only be realized with a National Government such as the one presently in office, committed to transforming the lives of Indians—and, most importantly, through the active participation of our citizens.

After all, it is great civilizations and their people that leave enduring legacies in their cities.

Nandini Bahri Dhanda is an Interior Architect by profession and an active blogger.

From an Army family she has lived across sixteen states in India and travelled extensively around the world. Her interests in art, culture, history, and politics, is coupled with a passion for connecting and conversing with people from all walks of life.