Last year, India exported USD 4.3 billion worth of beef, a number expected to increase by $200 million this year. Today, India exports to 65 countries where its beef competes with meat from all over the world.

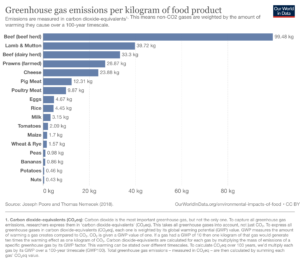

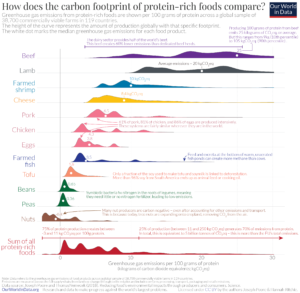

The largest meta-analysis of global food systems to date was published in Science by Joseph Poore and Thomas Nemecek (2018). In the study, the authors looked at data from more than 38,000 commercial farms in 119 countries.

CO2 is the most important Green House Gas, but not the only one – agriculture is a large source of the greenhouse gases methane and nitrous oxide. To capture all GHG emissions from food production researchers, therefore, express them in kilograms of ‘carbon dioxide equivalents’. This metric took into account not just CO2 but all greenhouse gases.

The most important insight from the study: there are massive differences in the GHG emissions of different foods: producing a kilogram of beef emits 60 kilograms of greenhouse gases (CO2-equivalents). While peas emit just 1 kilogram per kg.

Overall, animal-based foods tend to have a higher footprint than plant-based. Lamb and cheese both emit more than 20 kilograms of CO2-equivalents per kilogram. Poultry and pork have lower footprints but are still higher than most plant-based foods, at 6 and 7 kg CO2-equivalents, respectively.

For most foods – and particularly the largest emitters – most GHG emissions result from land use change, and from processes at the farm stage. Farm-stage emissions include processes such as the application of fertilizers – both organic (“manure management”) and synthetic; and enteric fermentation (the production of methane in the stomachs of cattle). Combined, land use and farm-stage emissions account for more than 80% of the footprint for most foods.

- Food production accounts for over a quarter (26%) of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- Half of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture. Habitable land is land that is ice- and desert-free.

- 70% of global freshwater withdrawals are used for agriculture.

- 78% of the global ocean and freshwater eutrophication is caused by agriculture. Eutrophication is the pollution of waterways with nutrient-rich water.

- 94% of non-human mammal biomass is livestock. This means livestock outweigh wild mammals by a factor of 15-to-1.

- 71% of bird biomass is poultry livestock. This means poultry livestock outweigh wild birds by a factor of more than 3-to-1.

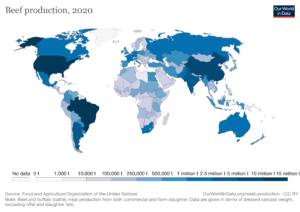

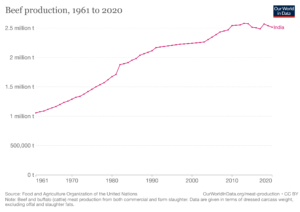

Globally, cattle meat production has more than doubled since 1961 – increasing from 28 million tonnes per year to 68 million tonnes in 2014. The United States is the world’s largest beef and buffalo meat producer, producing 11-12 million tonnes in 2014. Other major producers are Brazil and China, followed by Argentina, Australia, and India.

Globally, cattle meat production has more than doubled since 1961 – increasing from 28 million tonnes per year to 68 million tonnes in 2014. The United States is the world’s largest beef and buffalo meat producer, producing 11-12 million tonnes in 2014. Other major producers are Brazil and China, followed by Argentina, Australia, and India.

Beef and Buffalo meat production in India has risen to over 138 percent since 1961. India is the remaining top four beef exporter with steady exports expected in 2023. India exports large quantities of water buffalo meat (carabeef) to low-end markets in Indonesia and Malaysia.

In 2012, India’s annual GHG emissions were equivalent to 18 percent of gross national emissions. Livestock represented more than half of those emissions. In 2017, the agriculture sector contributed to 19.6 percent of India’s total GHG emissions, with livestock products like mutton (goat meat), eggs, milk, and poultry representing over 70 percent of those emissions.

Some researchers have projected that higher consumption of animal-based products is the primary driver of India’s increasing GHG emissions, worsening water scarcity, and intensifying land use. With a population of 1.3 billion (That’s four times the population of the U.S. living on one-third of the landmass.), India’s existing and future meat consumption patterns will have a serious global impact.

India’s 2022 production of carabeef (meat derived from Indian water buffalo) and beef is forecast at 4.25 million metric tons (MMT), up by 250,000 metric tons (MT), an increase of over six percent from the USDA official 2021 estimate of 4 MMT. Despite the lashing that the Indian economy took during the COVID-19 second wave (March-May 2021), the country’s livestock meat industry still fared well. India’s 2022 carabeef/beef exports are forecast at 1.5 MMT, up nine percent from the USDA official 2021 estimate of 1.3 million metric tons.

Farmland takes up more than 50 percent of Earth’s habitable land and the vast majority of that farmland is used for livestock and their feed. Farming is the leading cause of natural habitat loss, which is the biggest threat to wildlife. Reportedly, beef production is the top driver of tropical forest loss. Eating more meat means that more natural habitat needs to be cleared and deforested and the diets of people in high- and middle-income countries can be key drivers of global deforestation. Conversely, reducing meat consumption would free up land which could be restored to benefit people and wildlife and store carbon.

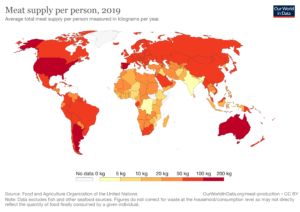

Since 1961, meat production worldwide has quadrupled as meat supply per person has almost doubled (from 23kg to more than 43 kg) and the human population has more than doubled (from 3 billion to 7 billion).

The number of animals slaughtered each year has consequently skyrocketed. The number of chickens killed each year has increased tenfold since the 1960s (from 6.6 billion to 68.8 billion), pigs have almost quadrupled (0.4 billion to 1.5 billion) and cows have increased from 0.2 billion to 0.3 billion.

Meat consumption is also very unevenly distributed. Just as richer countries tend to have higher greenhouse gas emissions, they also tend to eat more meat. For example, the average US citizen is supplied with 124 kg of meat per year, whereas in China, Nigeria, and India it’s 61 kg, 7 kg, and 4 kg respectively.

Studies indicate that beef is more resource-intensive than most other foods and have a substantial impact on the climate. Both the food producers and consumers have a role to play in reducing beef emissions as the global population continues to grow and as India’s beef production and consumption continue to grow.